The feature image, my painting Girls on the Grass presents females of different species free from the pressures of a patriarchal society enjoying lunch on the lawn. To convey the idea of sanctuary where humans and non-human animals alike can find a safe haven, I have drawn on Édouard Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (1863) as a source of inspiration. While painting I realized there must be a strong link between the animal advocacy and feminism movements. First most of the grass-roots animal activists seemed to be women. More importantly, animal food comes from females – either directly as their flesh or the flesh of their children, their secretions (dairy) or their eggs. This inspired me to take a feminism course.

One of the assignments for the “Activism, Feminism and Social Justice” I am taking at Carleton University, was to make a video. Never having taken a feminism course before I used the assignment as an opportunity to read Carol J. Adams’ landmark book, The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory (1990, 2000). I used Adams’ critical theory as the framework for much of the video, linking feminism, farm animal advocacy and veganism. Because I am an artist, I concentrated on Adams’ discussions of the visual tropes of sex, animals and meat that are widespread in visual culture, which she suggests are both evidence and reinforcements of sexism, speciesism and meat-eating as cultural norms within our Western society.

In her book, Adams builds a straight-forward case for vegan-feminism based on both women and other-than-human animals being positioned as objects rather than subjects within the Western patriarchal society, which still privileges men over women and humans over animals. Despite human rights advances, remnants of sexism and speciesism (as well as racism, homophobia, ableism, colonialism, etc.) are imbedded in our culture, largely unseen and unchallenged. Dominant ideologies are invisible because they are “the norm.” These norms are reinforced by institutions, cultural expectations and the common tropes found in visual culture.

Adams describes patriarchy is a gender-based system of privilege, power and oppression that is implicit in human/animal relationships. Adams says “A feminist-vegetarian critical theory begins…with the perception that women and animals are similarly positioned in a patriarchal world, as objects rather than subjects” (Adams, 2000, 180). In defining a critical theory she identifies four key components, which are explained below.

Meat and Virility

The first component of Adams’ feminist-vegan critical theory is that in Western culture, men should eat meat and women should serve it. Meat is the focal point of most meals, especially festive events, highlighting the normality of eating carcasses of animals. Meat-eating is a one way men can continue to assert their manliness in an aggressive and domineering performance. Adams notes that she has witnessed women being abused by husbands when they failed to serve meat for dinner (Adams, 2000, 48). These behaviours are imbedded in cultural expectations for manliness and the good wife and mother and reinforced by magazines, books, cookbooks, family and social experiences, advertising and media.

The Absent Referent

The second component of Carol Adams’ critical theory is “the absent referent.” An absent referent refers to something that is non-existent, undefined or paradoxical.

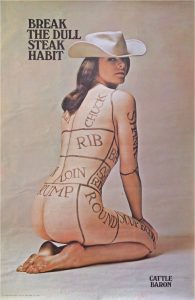

Adams argues that both women and animals are linked in that they both function as absent referents in the process of objectification, fragmentation, and consumption (Adams, 2000, 14 & 2010, 304). Women are compared with animals through metaphors and visual images that liken them to animals or meat. The “Break the Dull Steak Habit” poster (Figure 1) was used by feminists to protest against the 1968 Miss America Pageant, liking it to a cattle auction. The woman’s body is marked with meat cuts ready for fragmentation. Similarly, an abused women saying “I felt like a piece of meat” or Lady Gaga’s meat dress are metaphors for the female body as meat and an object of male consumption. The animal is the absent referent.

Other–than-human animals are also made absent by language when we talk about meat instead of corpses of dead animals; processing instead of slaughter and butchering. The absent referent cloaks the violence inherent in industrial agriculture and makes it easier for otherwise compassionate people to keep eating animals. Slaughter separates the meat-eater from the animal and the animal from the end product.

Feminized Protein

The third component of Adams’ theory is Feminized Protein, referring to eggs and milk, which are animal foods produced by manipulating the reproductive capacities of living females. The animals are oppressed by their femaleness into a “sexual slavery” on factory farms. “Even though the animals are alive, dairy products and eggs are not victimless foods” (Adams, 2010, 305). Feminized protein serves two functions in that it makes a link with feminism through the exploitation of the female reproductive system and motherhood, and also makes the case for veganism vs. ovo-lacto vegetarianism.

Sex Sells

The fourth and final component of Adams’ critical theory is that sex sells just about everything. Common visual tropes of sex, animals and meat are used widely in advertising. “Make it sexy” or “add some sizzle” are ways of saying make something more appealing. Although commercial advertisements are clearly rich in suggestive tropes so are the visuals for promoting both feminist and animal rights causes.

I hope you enjoy the video!

References:

Adams, Carol J. 1990 & 2000. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory, Tenth Anniversary Edition. New York: Continuum Publishing Company.

Adams, Carol J. 2010. “Why feminist-vegan now?” In Feminism and Psychology 20(3): 302-317.